All in procession

Louis Mason

First it is dark and your body is in darkness. You cannot see anything around you at all. If you use your hands to explore the floor you will find that it is rough and cold, like unworked stone. You can hear your breathing and the other natural processes of your body, and these provide a minimal structuring to this lightless, stone-floored world. The steady expansions of your chest, your heartbeat and digestion, the roughness against the pads of your fingers, the chill in the air around you as it moves over the skin of your chest and face—you feel these deeply and clearly. In the darkness, with nothing to contain them, your senses expand outwards from your body into black emptiness. This is easy and natural; in fact, it feels like losing consciousness. You expand and expand, until your chest rising and falling and your heart beating become the anchors for the part of you that moves outwards at incredible speed. Your centre is small and very far from you. Gradually you become aware of other breathing in the darkness around you, and this awareness comes with complicated feelings; of joy because the others are here too, but also of trepidation, because in this instant the scope of your expansion has become relational. When you reach out your hand, they are there to welcome you with mutual touch. Already you can distinguish between them. Their characters are obvious. You think that nothing has ever spoken as loudly as this first cycle of touching. When you press yourself into the chest and belly of any of them you can feel their breath swelling and escaping, their heartbeat and digestion. You think that, over time, these processes might synchronise with your own, and that if you could modulate your body and slow down its natural rhythms, you might be able to fade into this strange system of equivalence. You think that the others must be doing the same thing. Eventually you lose consciousness.

The next time you wake someone has made a space for a fire, and the scene is illuminated by warm, crackling light. The fire is small and guttering, really it looks as though it could go out at any moment. But every time the flames die down and the light dims, someone leans in to blow on the embers or to feed in more fuel, or moves their body to shelter it from the wind. In the dim light the contours of the stone space are concretely revealed. It is a small and natural-looking cave that extends off into subterranean darkness in one direction and opens onto the black and empty outside at its mouth. So you have your territory. Any expansion now will need to take place in another space, brought into being by an act of hallucinatory will, with eyes firmly closed. Everything that you encounter from this moment will be definitively either eyes-open or eyes-closed. Visions and dreams. You think that maybe the dream will find its true form by cycling between these states, moving from one to the other, in and out of consciousness, with each transit working to embellish and excavate new and deeper dream spaces. In the light of the fire you can also see the bodies of the others, and they are monstrous, barely human. One has their chest broken open and when they sing, the sound is a scream of deep psychic pain. One has a face that is just one long, thick proboscis, no eyes or mouth visible. They snuffle along the ground, walking in slow, aimless circles around the fire, whispering to themselves. One is only the outline of a human, an outline that flickers with blood-red light and buzzes like an insect. You look at them all (there are maybe twenty), and then you look down at your own body, which you realise is in a constant cycle of dissolving and recohering. Your skin, bones, and musculature bubble and deform, fly away as gaseous emissions, and then reform again. You cannot feel this happening and there is no pain: it took looking down and focussing your vision on your arms and chest to notice. And when you reach out to the others, their touch is the same as it ever was—warm and gentle, full of love and curiosity. So the dream is layered over this interface of communal touch, just as it was before. In the dream any body is possible.

In the dream all the bodies flow together like water. They are hijacked by strange intelligences from outside the circle of firelight; they perform songs that tear them apart; they associate with the wind that scatters them, or with the sky. When they see the sky for the first time, they will fall vertically upwards into the stars and the blackness and expand outwards again to the point of obliteration. But no matter what happens to them, no matter how completely they dissolve, they will always be able to find their way back through this system of communal touch, which forms the essential grammar of the transformations, and lets them exhibit (even if only between one another) something essential about themselves.

After the first fire there is a long period of sleeping and waking, thousands of transitions between the two, so that you become accustomed to the slippage between them, to distinguishing between the visions that are proper to each. This is also a period of consolidation. The cave goes through important changes, and so do the bodies that inhabit it. The rough stone is smoothed and carved into a large proscenium stage, and furniture is constructed and installed; large folding screens and flats that can be used to block vision to specific areas of the platform, a scaffold structure that supports a latticework of thick timber framing above, trapdoors and false walls that lead into hollows and tunnels carved into the solid stone below. They install mirrors and lenses and complex lighting systems: spotlights, strobe lights, and amplification machines. Still pools of water and thick black oil, tangled piping and pumps to move liquids through the space, to flood or to drain it, to fill vast transparent tanks. Furnaces to heat these to boiling point. Cranes and other pulley devices that allow for the suspension and movement of bodies and other heavy objects through the negative volume behind the arch. All this takes decades or centuries, it is difficult to tell. The passage of time is ordered by the cycling of opacity (unconsciousness) and existence in the dream that they all share. As the grammars for complex expression multiply, the bodies cohere into more or less standardised human forms. There is no longer any need to break yourself into pieces or to dissolve—the same effects can be achieved with elaborate costuming and careful linguistic invention. The songs are no longer screams; the scream is notated and complexified, discovering its own capacity to remake the world as form and representation.

One day you wake up beneath the glare of the spotlights as the others are beginning the night’s performance. Each takes their place on the stage, marked in advance in relation to all of the others, and with its own lighting and associated suite of special effects. You watch the performance, and perhaps you also perform with them, and understand yourself relative to their expression, which is true and clear. The stage allows you to say things about yourself, very specific things; you can talk about love and fear (for instance) in ways that are extremely precise. The first language of touch is still present beneath things, but it is more private now and more intimate, touching takes place away from the stage and the lights and mechanisms. When you say something about love or fear you sometimes speak for the other bodies too, because they are now so much more like you. Your body is no longer exactly itself and has become more lucid and more eloquent. When you speak for yourself, it is in private. When you speak for yourself, you are almost asleep or just waking, in a dark space, somewhere away from the performance, and the old systems of touch and breath emerge again, at the edges of opacity. You associate them with the blurred half-thoughts that crowd the mind before sleep. And meanwhile the dream that you all share spits forth its life-literature of saints and monsters and heroes, of struggle and compromise, of recursion; funny and abject stories, stories of terror. The same stage can be used to tell the story of the body broken apart, the body with its chest caved in, the body that buzzes like an insect and moves beneath red lights, and also the story of the first touching, the story of infinite expansion, the story of the kindness of the others. It can tell you all of these and infinitely more. They all make use of the same props and the same mechanical systems, the same mirrors, the same masks, the same vibrating and negative volume that extends backwards behind the vertical plane of the proscenium arch.

During this period your sleep is often induced by another, and the method that they use to render you unconscious is obscure—hypnosis, anaesthesia, soporifics, massage, whatever it is works quickly and it is absolutely effective.

-

When you wake again it is inside your own dream, for the first time that you can remember. In this dream the theatre and the cave are gone. They ended a long time ago—no great apocalypse or crumbling, only stories packed into stories until all reference to the original bodies was lost. In the dream your eyes have been opened outwards into something that looks like a hall of mirrors, in which scenes and characters are nested in infinitely repeating formal arrangements. The scenes repeat, moving backward away from your opened-out eyeballs in an endless stream, and they are fractally complex, so that when you focus on them each unfolds into infinite permutations, and each of these does the same and so on. You could spend your entire life chasing these images, recombining them, ordering and sorting them, making them play by the rules of narrative that you developed together; you could stuff the stage with them, you could drag each of them through the space behind the arch and you would have a new story every time. Something similar happens in miniature in the empty space of your opened-out eyes. After a brief period of confusion you decide that these eyes are no longer of much use to you. They can tell you nothing, though you could easily search through them for images of anything. The specificity of placement and relation that is proper to the stage has been erased. In your dream you find that you cannot close your opened-out eyes, so instead you choose to ignore the visual data that flows through them into your brain. The infinite stream of images is placed at the same level as the other automatic processes of the body.

Once this is done it is easier to focus again on the other senses inside your dream. You find your way across the rough stone floor of the cave by touch and smell. As you move nearer to the centre there is the warmth of the fire on your face. This is how you orient yourself, warmth on your face and chill on the skin of your back. You know not to venture too close, since without usable eyes you might overstep and hurt yourself. Your hands find another body, unconscious, dreaming its own dream. You think that if you explored its form you would find it cracked open, vibrating under red lights, its face would be the proboscis, its song would be a scream. It dreams of the theatre where it can tell stories about transformation and equivalence. The space that affords it lucidity. Or maybe it dreams of something else, you have no way of knowing, since this is your dream, your first alone, and there is nothing that intrudes here from any outside. You think that if you are to remain in this place for some time you will need to find some new way of recording your history and your own transformations. The stream of images flows through you uninterrupted, harsh and brilliantly white.

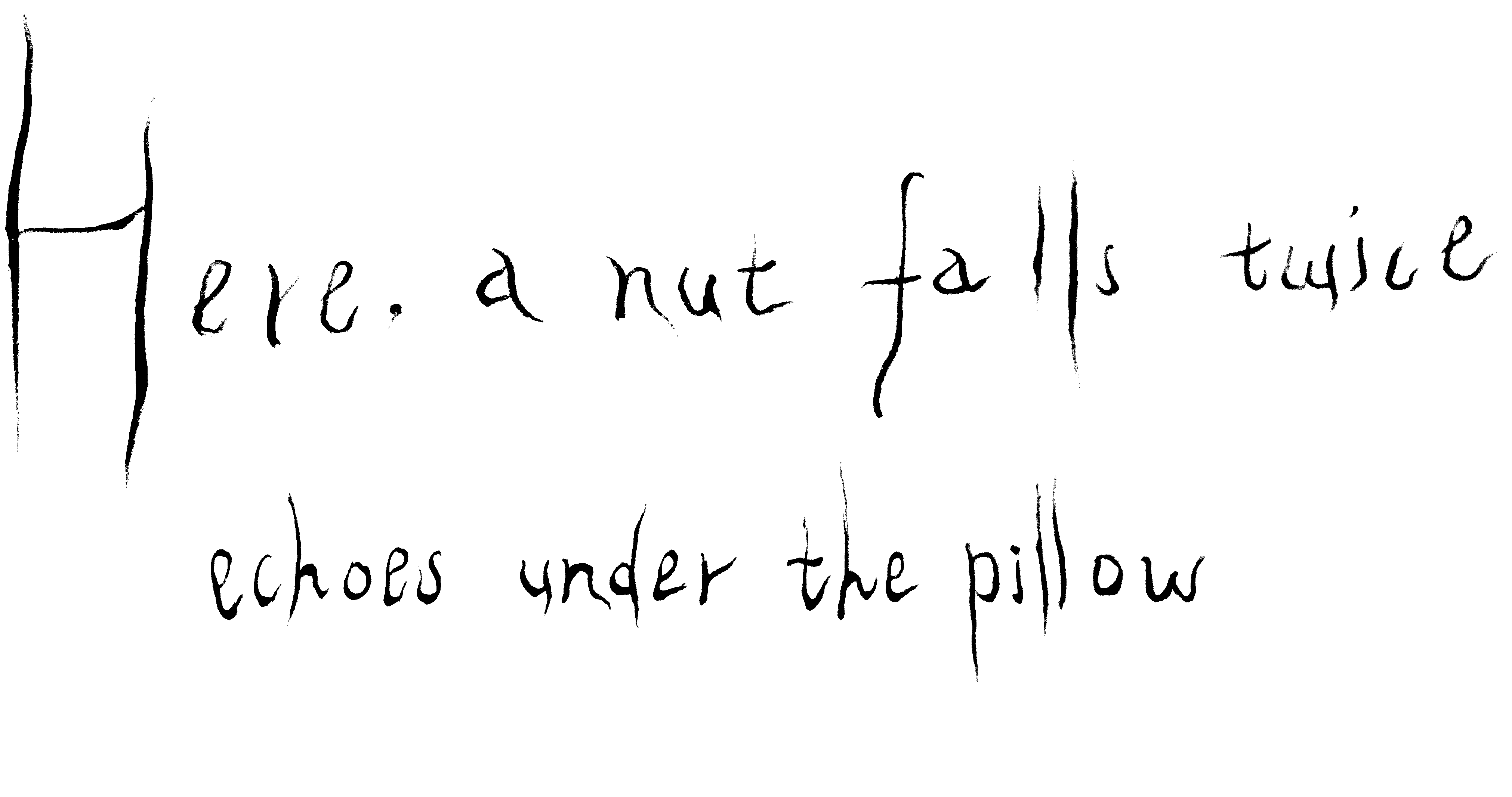

You scrabble along the rough floors blindly, looking for something that you can use, and sometimes you find sleeping bodies and bedding, splayed out around the central fire in concentric circles. Your blind movements are clipped and oddly birdlike. After a very long time, you find a section of floor that is softer and more yielding than the stone you are accustomed to. It is just as cold, but when you press into it you can make imprints on the surface with your fingers and nails. Which you do, moulding handfuls of the soft, cold matter into a small collection of disks and vertical cylinders, which you then press into and mark with your nails. Since it is only you in the dream, the marks are not a language, but there are repeating groupings and touch-images that you return to as you work, as the mood takes you; there are jokes and expressions or loneliness or warmth. You are not afraid, since this is all just a dream, and soon you will wake up and be back in the collective dream of the theatre, with the others. Your opened-up eyes will regain their capacity to distinguish, and you will tell stories about touch and breath. In the meantime you sculpt these small objects, thousands of them, from the obscure material that surrounds you, cold, soft, yielding, and stretching off from where you sit in an unending surface. The warmth of the fire is at your back, and the soft sleep sounds of the others. You work and work and wait for the dream to end.

But then something strange happens. As your blind fingers move across the floor, they find something other than the flat, soft, cold stuff that you gather up—they find a small, round object, like a sculpted disk, impressed with the complex markings and indentations from another hand and another set of fingernails. You run your hands over it in shock, but there can be no doubt about its essential form. The harsh light hums in your eye sockets. You try not to panic. Is it possible that you have found one of your own creations that you forgot was there? Maybe you have traced a wide circle around the fire, and this is an early prototype from when you first encountered the soft surface? But when you run your hands over it you know that this system of marking, obviously specific and coded, is alien to you, that it must have been created by another, by someone else moving around out here in the dream, at the edge of the circle of warmth. For the first time you wonder if the cave really is as you remember it. If the floors are stone and the light is firelight, dim, guttering, warm orange. There is a flash of a hideous image: the cave lit up in white light so harsh and so bright that everything around you is reduced to black shadow or burning glare, and of you squatting in the brilliance, blind, pressing your hands into the soft, cold surface and pulling them forth, again and again. In the vision the white electric light is fixed inside your skull and spills in a torrent from your eyes. You are paralysed; you cannot reach forwards because you might find more of these alien objects, more evidence of this other. You strain your ears for movement behind you, from the sleeping others, but there is no movement at all, only breathing, and the soft heat on your back. You think that you need to wake up, and slowly move to replace the small, soft thing where you found it. And then you feel a new warmth, exactly like that of the fire but instead coming from in front of you, washing over your face, slowly approaching, extremely slowly, and realise in a crystal moment of panic that you need to wake up before whatever it is reaches you. And you do wake up.

-

In the theatre the bodies all move in procession. They cycle between the opacity of sleep and the lucidity of the collective dream. They sing about the early period of touch, breath, and monsters, of infinite expansions, and they sing about the building of the theatre and its mechanisms and devices. They sing about their own physical transformations, about what they have in common. The audience is enraptured. The collective history of the bodies is beautiful, and the audience is discreet and appreciative. They smile to one another or simply lie back and enjoy the show. Sometimes the songs are about what will come after the theatre, what will happen when the machines rot and break down and are made obsolete, but these are more obscure, and there is little firm agreement as to what can be said.

When the performances finish for the night the audience will mill around in the darkened rooms and entrance foyers and corridors of the theatre and discuss what they saw. Sometimes they make their way up onto the stage. It all takes some time to process; to correlate the performances with their own lives and their own struggles and triumphs, and it can help to talk things over with others. But over time, generally several hours, they will begin to exit the old stone building and filter outwards into the sleeping city, slowly at first, in twos and threes or singly, and then in larger groups, until each has made their exit out into the mist and the softly swelling morning light and disappeared from view.