More and more a hive: Drift (in)between’s overnight lullaby of imaginary landscapes

Jared Davis

A travelling oasis

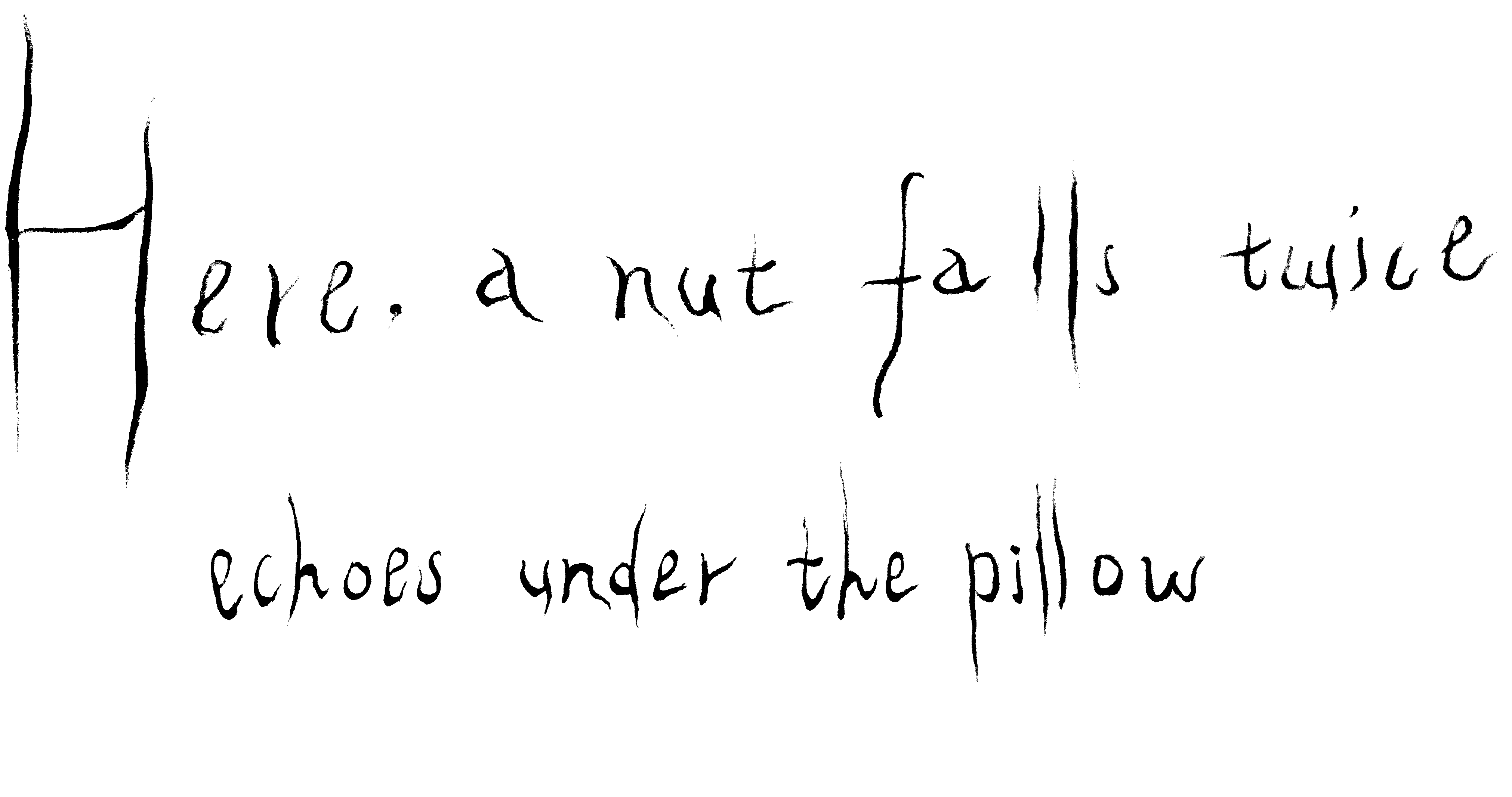

Drift (in)between was a living world of fiction, a petri dish for audiences and performers that inscribed an altered sense of time, dreaming, biology and memories. As an overnight performance in the ICA’s theatre space, the work presented our bodies as a site for calcifying narratives and stories. Evoking questions on the visceral, time, and the overlap of these threads through poetry, Drift (in)between was a journey through ‘imaginary landscapes of inaudible frequencies, sleep-inducing rhythms, dream echoes, lullaby of nightmares, shimmers of darkness, nocturnal wanders, and bedtime tales.’

Over the course of eight hours, ten collaborators melded into one performance body, and as a spectator, it became difficult to distinguish any separate membranes between one artist and the next. The artists and their live interventions joined with one another like synaptic connections in a new collective mind. In a darkened space—with dispersed synthetic-organic sculptural forms, and blanketed by sonic ambience as well as occasional light beams—the cast of the show took us to spaces ranging from gentle to tense, soft through to surreal. There was electroacoustic music with soft vocalisations, fantastical narrators telling tales through organic extensions of themselves, such as a light-up soft sculpture-cum-prosthesis. A slowly trudging being with screens protruding from their shoulders on a pole climbed through still listeners. Drone moments ushered the bodies scattered throughout the space into early sleep phases, only to shift into sonic climaxes of red strobe lights. Nordic lullabies, the gentle dripping of water onto metallic dishes, and acousmatic moments of environmental sounds all immersed listeners into a state of temporal suspension. It gave one the feeling of entering a humid and dense forest ecosystem, growing on plastics and technological relics to form new symbioses.

Throughout the night, the performers’ individual identities dissolved, and audience members slowly stopped wondering about the distinction between one performance fragment and the next. The artists had left their earth-bodies at the entrance to the theatre, adopting pseudonyms and fictionalised accounts of themselves. They became creatures and non-human forms: ‘a big loud whale full of colours and brightness slowly waking up inside of a coconut shell’, or ‘a piece of dancing willow-leaf that travels with the wind’, or ‘a travelling oasis made of various shapes of love particles’, etc. Poetry and poiesis were the core generative tools of the show.

Drift (in)between’s emphasis on collective embodiment and the organic spoke to current ontological upheaval, following a period of viral contagion in which communion was rethought. It evoked contemporary notions of our biological interdependence, as well as the malleability of time. Nothing makes sense as it once did: our somatic experience is increasingly dematerialised through communication technologies, and nature is not immutable. The present seems like an uncomfortable interregnum, in which we are undertaking a techno-organic metamorphosis. There is a general discomfort we have as a species when things are out of our control, or our sense of understandable order. We’ve solidified an ideology and culture, by basing our concept of humanity on a notion of free will, as well as a supposed mastery over nature. This was turned on its head during the pandemic, and while on a superficial level things have been wrenched back to an old order, what lingers is a kind of gothic horror of our environment: a fear of a landscape and ecology that we do not, and never have, ruled over as free agents.

The fevered acceleration of technological mediation into our daily lives brought about by the pandemic has not quelled. While we’ve returned to physical gatherings over livestreams, and talk of the ‘metaverse’ reads like an anachronistic gimmick, there is a general atmosphere that our sense of self as individual organisms is being ruptured by technology in a way that we don’t yet fully appreciate. Take for instance the general apprehension around AI and the ontological crises of agency that it raises. We are becoming more and more of a hive, whether or not our minds are ready for it.

Every object an hourglass

One thread that runs through all this relates to notions of time and our histories, as well as the flaws and cracks in our organic understandings of these, which are elucidated by Yen Chun Lin. Philosopher Thomas Moynihan presents a dizzying thesis in his 2019 work of theory-fiction Spinal Catastrophism, that outlines the relationship of upright posture in human beings as a crucial aspect of the nature of our consciousness. For Moynihan and the authors he evokes, our body is a site of inscription for our history—like the rings in the trunk of a tree—and our phenomenological experience is bound to the evolutionary aberration of upright posture. Through a number of conjectural twists and turns, references to obscure citations that may or not have been fabricated, and an eerie fixation on the spine, the book provides a creative dissection of some of the ways in which we are due to rethink the fundamental elements that make us ‘human’. The book paints an evocative image of our central nervous system as a serpentine creature: a spine, brain and eyes, covered in an ill-fitting flesh prosthesis. Spinal Catastrophism mirrors the ungraspable and evocative style that we see in the performance-experience of Drift (in)between. It carries an air of scholarly rigour, however its sources cross between the realms of fact and fiction like soluble compounds crossing into fats. In terms of style, the book is not unlike the intangible storytelling of Drift (in)between. It too is concerned with our embodied sense of time, and reads as much like a fever dream of myth in a world that no longer makes sense.

Like a garden full of plants and a pond full of fishes

One of the more evocative sections of Spinal Catastrophism examines philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s writing in The Monadology, a text that proposes that the universe is made up of individual units called monads. Monads are like tiny, indivisible particles that are not physical, but rather have mental properties such as perception, consciousness, and will. Leibniz argues that these monads are constantly interacting with each other, but they do not influence each other directly. Instead, each monad is like a mirror that reflects the entire universe from its own unique perspective. This means that every monad perceives the world in its own way, and that there are countless different perspectives on reality.

Leibniz’s infinitisation of biology, a site of interest for Moynihan, brings to mind the unending sense of biological multitudes evoked in Drift (in)between. The German polymath notes: ‘Each portion of matter may be conceived as like a garden full of plants and like a pond full of fishes. But each branch of every plant, each member of every animal, each drop of its liquid parts is also some such garden or pond.’ (Leibniz) In an extension of this train of thought, he comments that ‘there is nothing fallow, nothing sterile, nothing dead in the universe.’ Moynihan elaborates on this idea: ‘if all life comes from other life, then, as far back as you can go, there is always life. What this meant is that the inorganic simply didn’t exist.’ (Moynihan 84-5)

Here is a theoretical precedent, or one of many, for thought processes on the collective biological interdependence that Yen Chun Lin’s work evokes. These weird linkages between biology and temporality are creatively sutured by Moynihan. When discussing Leibniz’s aforementioned text, he speaks of ‘an exploded-view cross-section of radically disarticulated moments of total time: each internal organ or external species a piece of suspended historical shrapnel.’ (Moynihan, 94) To the audience members of Drift (in)between, we were implicated as visceral markers in such an abstraction of the temporal experience. Our organs are at once individual units, but collectively breathing, seeing, smelling, listening together. We carried into the performance our histories and memories, our life chronologies, and were guided into a slowed and reconfigured embryonic state.

Part of this text was written in collaboration with ChatGPT